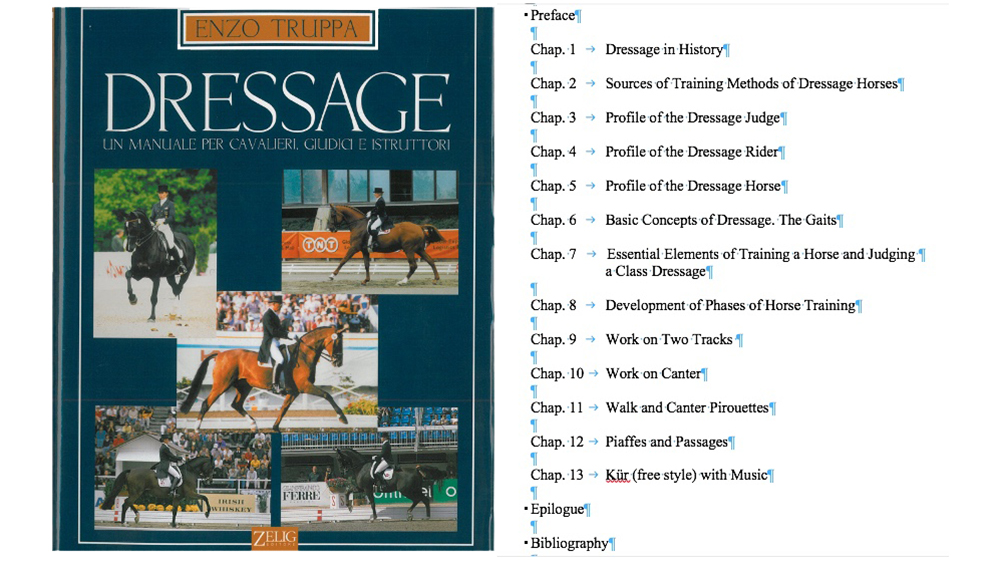

Dressage.it is very proud to present the English version of Doctor Truppa’s book, DRESSAGE.

Our followers and readers will find, monthly, the chapters of Truppa’s work, following the order reported here below.

Do not miss your date with the best Dressage…

January starts with a very interesting Preface which presents Truppa’s philosophy on the discipline and chapter 1 of the book.

Table of Contents

Preface

Chap. 1 Dressage in History

Chap. 2 Sources of Training Methods of Dressage Horses

Chap. 3 Profile of the Dressage Judge

Chap. 4 Profile of the Dressage Rider

Chap. 5 Profile of the Dressage Horse

Chap. 6 Basic Concepts of Dressage. The Gaits

Chap. 7 Essential Elements of Training a Horse and Judging a Class

Chap. 8 Development of Phases of Horse Training

Chap. 9 Work on Two Tracks

Chap. 10 Work on Canter

Chap. 11 Walk and Canter Pirouettes

Chap. 12 Piaffes and Passages

Chap. 13 Kür (free style) with Music

Epilogue

Bibliography

PREFACE

Dressage can rightly be considered an art whose main goal is to make the horse pleasant to ride, and thus relaxed, elastic, attentive, and obedient. The exercises that allow for reaching that goal are aimed, on the whole, at obtaining a gradual lowering of the haunches to make the horse able to “bear weight.”

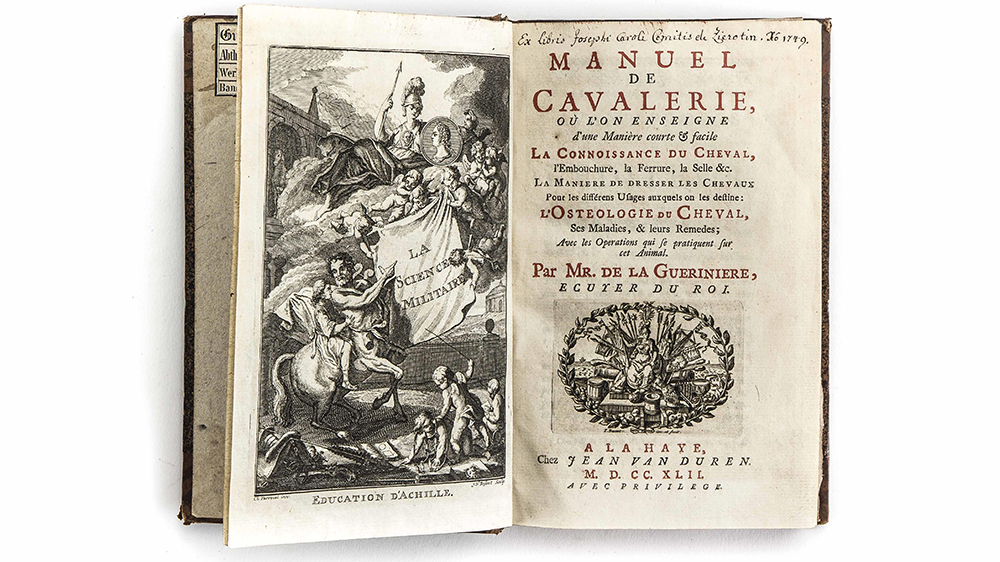

“If that is not met, the horse will be neither comfortable in his movements nor pleasurable to ride” (De La Guérinière 1688-1751).

Although we are seeing an increasing number of variations in the range of exercises used in training a horse, due also to the increase in quality of breeders, the basic principles of dressage have remained unchanged over time.

There are countless good books on dressage in various languages, and many of them also cover the “secondary” aspects of horse training, such as nutrition, mouthpieces, stable care, and also veterinary problems.

This book does not aim to cover such a broad range of subjects, since it has been written with the main goal of favoring a common language among riders, trainers, judges, and stakeholders, and secondly, of representing a reference point in the training of a horse and the consequent judgment that is expressed in dressage arenas.

The text has been developed also keeping in mind the point of view of a dressage judge, at times explaining what the correct presentation of the horse should be, and what are the most frequent errors detected in the execution of various figures. In any event, I hope that riders and trainers can also find it useful. On many occasions, we have not limited ourselves to presenting the “ideal” to show the judge, but also methods and exercises through which to attempt to reach that goal.

All of this is presented with the maximum respect for “classical principles” and using definitions, terms, and references contained in the “holy scriptures” of dressage, meaning the rules issued by the International Equestrian Federation, that are included in the FISE National Regulation for Dressage.

I believe it may be useful to provide some suggestions for those who are preparing to read this book:

- there is no recipe for “instantaneous” dressage. The secret of success in this sport is to “progress slowly, but surely.” It is only patient and proper daily work that will ultimately produce significant results. Whoever thinks they can avoid this patient daily dedication by using “special means and effects” or various types of shortcuts (such as draw reins), will never train a dressage horse in the truly correct way.

- this book, among other things, tends to stress the basic aspects of training a horse and its consequent judgment in the arena, rather than the easy recognition or the simple listing of errors in the execution of figures (for example, improper changes in canter, extended trot breaking in canter, etc.). The comprehension of this aspect is of fundamental importance for whoever wants to undertake dressage at the international level in any role (rider, trainer, or judge).

Lastly, allow me to say that, if a horse is trained properly according to the “classical principles” (“Happy Athlete”) which I have followed fully in writing this work, all you will need is a snaffle (later a double bridle), a saddle, spurs, and eventually, a whip.

Nothing more! There is an old saying that goes like this:

“where arts ends, violence starts”

Chap. 1/DRESSAGE IN HISTORY

Since ancient times, the art of horse-riding has been enormously developed, as can be seen for example from the book by the Greek statesman and general Xenophon, written around 380 BC. In Xenophon’s book there are already references to Simon of Athens, who in turn had written a very detailed treatise on the art of horse-riding, which unfortunately has been lost. Whoever has studied Xenophon’s book, written 2,400 years ago, cannot but be impressed by the precision of his explanations and the acumen in reporting on the moods of the horse. His training method was based on intuition and gentle treatment of the animal, which unfortunately, as we will see, was not always implemented by the great masters who succeeded him. Xenophon cites Simon of Athens: “For what the horse does under compulsion,, is done without understanding; and there is no beauty in it either, if one should use whip and spurs or similar means to force a dancer to perform, there would be a great deal more ungracefulness than beauty in either a horse or a man that was so treated.”

With the fall of the Greek Empire, the cultural value of many artistic activities was lost; the art of horse-riding continued to decline, to the point of becoming almost insignificant.

Xenophon has the merit of having preserved the idea of equestrianism until our times, because it was his book that constituted the basis on which the art of equestrianism was founded during the Renaissance.

Approximately two thousand years later, in the sixteenth century, the art of equestrianism, forgotten for so long together with other artistic activities, returned to light.

As the great masters in the field of painting and sculpture began to flourish again under the Italian sun, the same happened with the reawakened art of horse-riding. It was in fact reintroduced by the Neapolitan nobleman Grisone, recognized by his contemporaries as the father of the art of equestrianism.

For reasons of completeness, it should be noted that at that time, equestrianism was complementary to the activity of war. Battles were fought on horseback, and thus the art of riding became “vital,” so to say, for the conduct of military activities: the half-pass served to avoid the enemy’s blow, the pirouette was useful to defend oneself if surrounded, the passage was a parade step, and the “airs above the ground” (courbettes, caprioles, etc. still practiced at the Spanish Riding School of Vienna and in Lipica) served to extricate oneself from critical situations during combat.

Grisone had studied Xenophon’s book in depth, and in fact he repeated almost word for word the instructions that regard the seat of the rider and his aids, for example. His idea, though, was to control the horse through force, as demonstrated by the numerous and rather severe mouthpieces he invented. This can be partially attributable to the circumstance referenced above, that is, the use of the horse as an instrument of war, and thus not being able to “allow” oneself to perform movements in a non-precise manner.

The most famous of Grisone’s many students was certainly Pignatelli. He held the position of Director of the famous Academy of Equitation of Naples, where Pluvinel was also accepted as a student from France.

Pluvinel, who would later become the teacher of Louis XIII, was a follower of Pignatelli’s philosophy, but he certainly adding something to Pignatelli’s principles, as a result of his own personal experience. Contrary to his teacher and predecessor, he pointed out that each horse had to be considered individually, and the treatment reserved for it had to be based on intuitions that could only be individual, since each horse is different than others. Thus, he substituted much more human principles for those based on force that were common in that period. His ideas were put into circulation with his book Manège du Roi that appeared in 1623. At the beginning, that book was ridiculed, but as the years passed, Pluvinel principles were accepted and it can be said that in fact he prepared the field for the famous François Robichon De La Guérinière, who would later become the greatest master of equitation of France.

The practical effect that derives from progressing towards more humane systems in training horses meant that the doctrine of the Duke of New-Castle, not exactly inspired by the same philosophy and published in a rather elaborate book, did not create a lasting base in the art of equitation in England, also considering the cruelty inherent in his methods.

The influence that Grisone, Pignatelli, and their students had on equestrianism began to dissipate. Indeed, at the beginning of the eighteenth century, equestrianism was almost exclusively influenced by French masters, and the greatest of them all, De La Guérinière, produced perhaps the most revolutionary book on equitation of all time.

Unlike the publications of his predecessors, the clarity and ease with which De La Guérinière’s book can be read are truly exemplary. He based on work on simplicity and on concrete facts in order to be understood by his readers. There is no need to discuss the teachings of De La Guérinière in detail in this chapter, not because the subjects are not of great interest, but because modern equitation, as applied today and as we will see later, is in reality based on the same tenets.

With the advent of the Revolution in France, De La Guérinière’s principles disappeared. Moreover, the Napoleonic Wars, unfortunately, marked the end of the various equestrian academies in European courts; only the Spanish Riding School of Vienna ended up preserving the methods of De La Guérinière, until recent times.

The merit for this was due principally to the influence of Max Ritter Von Weyrother, a truly exceptional horse man, who led the Spanish Riding School of Vienna at the beginning of the nineteenth century.

His influence on the art of equestrianism went beyond the confines of his country, and was felt especially in Germany, where Seidler, and even more so Oeyenhausen and more than all Luis Seeger, were his disciples. The latter had such an influence in their country as to counter the doctrines of Baucher and his disciples Plinzner and Fillis, who were unable to influence the art of equestrianism in that country.

A brief parenthesis is necessary to stress the fact that, once the use of horses for military purposes disappeared, the art of equestrianism also suffered from an undeniable decline, and dressage essentially survived in France thanks to the circus performances of which Baucher and Fillis were the main protagonists at the time. This highlighted a substantial and irremediable difference of views between circus dressage (essentially not based on an “athletic” activity of the horse and the consequent use of its back and hind quarters) and classical dressage, that at that point was preserved – as stated – only thanks to that marvelous equestrian institution that is the Spanish Riding School of Vienna.

More than anything else, however, it was Gustav Steinbrecht’s book published in 1885, Das Gymnasium des Pferdes, that was based on the theories of Seeger and Oeyenhausen, which constituted the basis of modern dressage as it has come to us today and as it is presented in the rest of this work.

To return to the methods of Baucher, and Plinzner, one of his followers who worked in the royal stables of Berlin from 1874 on, they tended to close their horses, as advocated by Baucher, destroying every impulse, every desire the horse itself has to go forward. In truth, his followers justified these methods by citing the fact that, at the time, Plinzner had to train horses for Emperor William II of Germany, who was forced to ride his horses with a single hand due to a problem to his arm.

James Fillis was introduced to Baucher’s methods in France, after he spent twelve years as the head instructor at the Military Academy of Petrograd and appeared for the first time in Germany in a circus in 1892. It should be said that Fillis excited the admiration of the circus spectators and also found many followers among the riders of the time, who would have liked to see those methods applied in military training. Undoubtedly Fillis was a great artist, but he was more interested in the evolution of circus equitation than the basic principles of classical equitation, where all of the movements are based on precise laws dictated by nature. The proof of this is given by the many “unnatural” movements that Fillis himself presented, such as canter on three legs, the backwards canter, and the Spanish walk. The fact is, that when he died in Paris in 1913 he was forgotten by most, as was his principal teacher Baucher, while the methods of De La Guérinière, preserved by the Spanish Riding School of Vienna and then spread through Seeger and Steinbrecht, are still flourishing today and constitute the basis for the principles that make up the rules in force today, as issued by the International Equestrian Federation.

We previously saw that the Spanish Riding School of Vienna had a great influence on the development of equestrianism in Germany, and at the beginning of World War I, the teachings of the German Cavalry School of Hannover were completely influenced by the methods practiced by the Spanish Riding School of Vienna, also thanks to its commander Gebhart.

But it is certainly Steinbrecht’s book “Das Gymnasium des Pferdes,” revisited and put back into circulation by one of his students (Von Heydenbeck) that constituted the basis for the German equestrian instructions, that in turn originated the current FEI rules, which present dressage must follow.